21 Jul 2025

Market memory can be short. Same time last year, we were fretting about weak deposit growth. Today, we are fretting about weak credit growth. We think one thing is common across both episodes. That while all eyes are on the RBI to resolve the situation, the central bank can only partly address the problem using the monetary policy levers at its disposal. Instead, the root of the problem, and the real solution, in both instances, lies elsewhere –the real economy and the composition of GDP growth. Let us explain.

Last year’s deposit drag was a two-fold problem –concerns on tepid deposit growth and compositional shifts (too few sticky deposits). Once inflation started to fall, the RBI loosened monetary policy, pushing base money growth up. Real deposit growth started to rise in early 2025. But did the RBI solve the entire problem? Perhaps not. Some rise in deposits would have happened anyway (the credit-deposit ratio tends to mean revert). And the deposit composition problem persists. There remains a noticeable risein callable bulk corporate deposits and a fall in sticky retail household deposits. This, we believe, is not in RBI’s control. Rather, it has its root in the real economy. That in the few years post the pandemic, return to capital (i.e. corporate profit growth) was higher than return to labour (wage growth), and this showed up in savings behaviour.

Fast forward to today, and the concern is weak credit growth. Can the RBI help? Yes, it can, and it has, by cutting the repo rate by 100bp, and infusing large amounts of domestic liquidity. Will it solve the entire credit slowdown problem? Likely not. Because just as the deposit composition issue had its roots in the real economy, the credit softness issue does too. Weaker GDP growth has lowered the demand for credit. And more importantly, the pivot from formal to informal sector growth has played a role too. With formal sector fortunes not rising as rapidly this year, the investment demand for credit (e.g. housing loans) will likely be tepid. With informal sector benefiting from better real incomes (both farm and non-farm), the need to take personal loans to fund consumption will likely be weak too. Credit growth is being squeezed from both ends. What’s the way out?

In the chicken-and-egg debate of who rises first, GDP growth or credit growth, we have a new contender –reforms. At a time when global supply chains are getting rejigged, if India can do the right reforms, it could become a meaningful producer and exporter of goods, which could spur investment, credit and GDP growth. The reforms include lowering tariff rates, signing trade deals, welcoming FDI inflows, and improving ease of doing business. A start has been made. But for impact, reforms need to run deep.

Market memory can be short. At this time last year, we were fretting about weak deposit growth. Fast forward to today, and we are fretting about weak credit growth.

We believe one thing is common across both episodes. That while all eyes are on the RBI both then and now, the central bank can only partly address the problem using the monetary policy levers at its disposal. It can’t resolve the problem fully.

Instead, the root of the problem, and the real solution, in both instances, lies elsewhere – the real economy and the composition of GDP growth.

Let us explain across both episodes.

Summer 2024 was laced with a string of commentary from the RBI and markets around two issues – weak deposit growth (leading to a rising credit-to-deposit ratio), and some concerns around compositional shifts in the deposit mix (too few sticky household deposits, too much callable corporate deposits).

As we explained then, deposits have two drivers – money created by the central bank (known as base money, M0), and money createdby the commercial banks (through the money multiplier process).

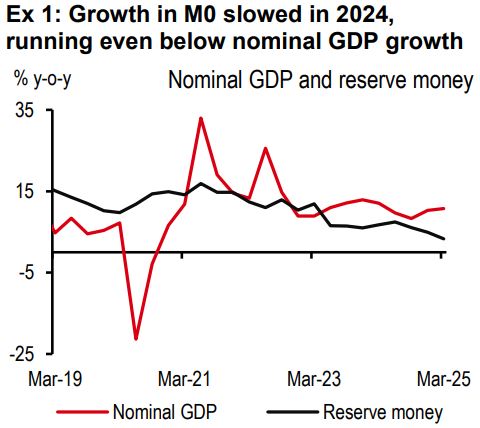

The money multiplier could not explain the weakness. In fact, the multiplier had gathered pace in that period. The weakness in deposits instead came from weak M0 growth. And, indeed, M0 growth had slowed over time, even running below nominal GDP growth (see exhibit 1).

Why would the central bank slow M0 creation? For most of that period, inflation was elevated, credit growth was rapid, and the RBI had been running tight monetary policy – raising rates with a hawkish “withdrawal of accommodation” stance, which is associated with tight liquidity. It didn’t help either that the dollar was strong, leading to central bank dollar sales.[@india-economics-05-01]

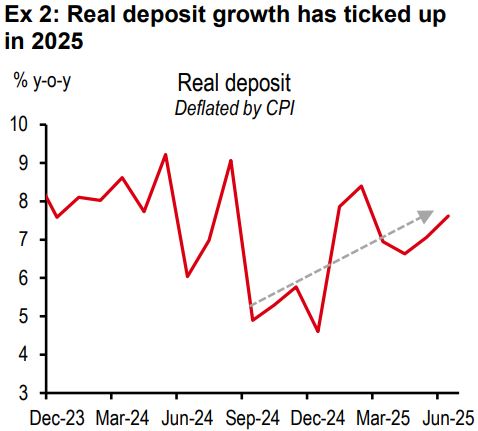

But then, literally speaking, the weather turned. The heatwaves ended, rains picked up, and inflation declined. Unsecured lending cooled off, and the dollar weakened, all of this making the RBI more comfortable with easier monetary policy, more liquidity, and faster M0 growth. Indeed, since early 2025, the RBI has cut the repo rate and infused domestic liquidity.

M0 growth (adjusted for changes in the CRR), is now running at 7.3% (as per June 13, 2025), in line with our nominal GDP forecast for the quarter, from being well under it over the last year. And real deposit growth has ticked up (see exhibit 2).

So can it be said that the RBI solved all of the problem? Two points worth noting here before we jump to any conclusion.

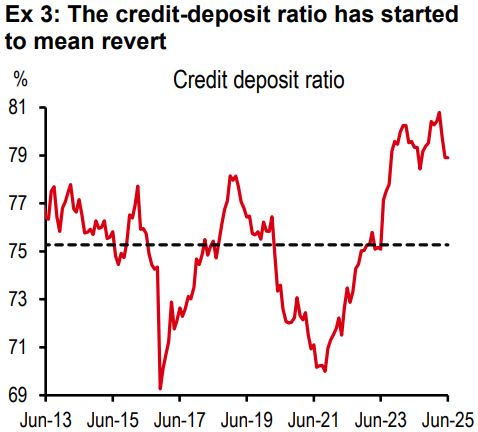

One, our sense is that some of the problems were auto-solved. The rather elevated money multiplier ensured that deposit growth eventually picks up as per the well-known maxim, ‘credit creates its own deposits’. In fact, as it always tends to happen, the credit-deposit ratio has started to mean revert (see exhibit 3).

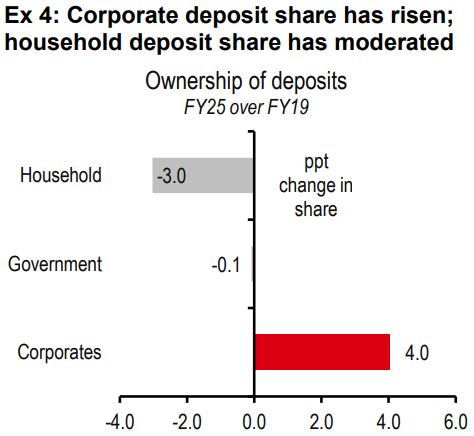

Two, the other half of the problems continue to persist. The compositional issue of ‘too few sticky deposits’ remain. There remains a noticeable rise in callable bulk corporate deposits and a fall in sticky retail led household deposits (see exhibit 4).

And this, we believe, is not in RBI’s control. Rather, it has its root in the real economy, i.e. India’s economic growth.

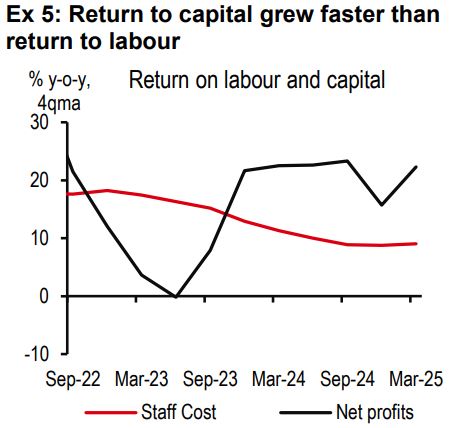

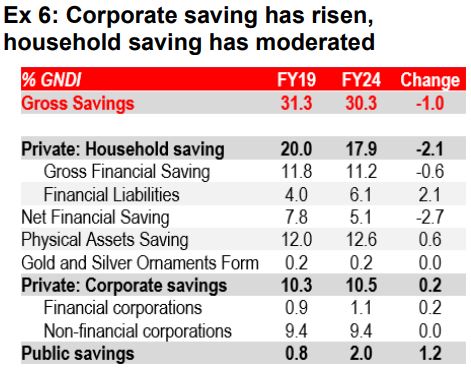

In the few years following the pandemic, return to capital (i.e. profit growth) was higher than return to labour (wage growth, see exhibit 5). This mapped well with India’s saving data, whereby corporate saving was above pre-pandemic levels, driven by strong profitability in certain sectors, while net household saving was lower than before (see exhibit 6).

All said, it is fair to say that the RBI helped raise deposit growth back up by raising M0 growth closer to ‘normal’ levels. But some of the rise in real deposit growth may have happened anyway following a period of high credit growth. And the composition of deposits issue lingers on, at the mercy of the real economy. As such, the RBI did lend its support, but could not resolve the problem fully.

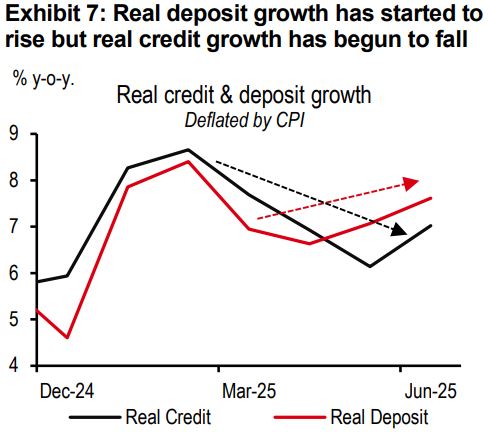

Fast forward to today and the concern has flipped on its head. Real deposit growth has begun to rise after a period of weakness, but real credit growth has started to fall after a period of strength (see exhibit 7). There could be many reasons for this, ranging from lower GDP growth to increased risk weights in unsecured lending.

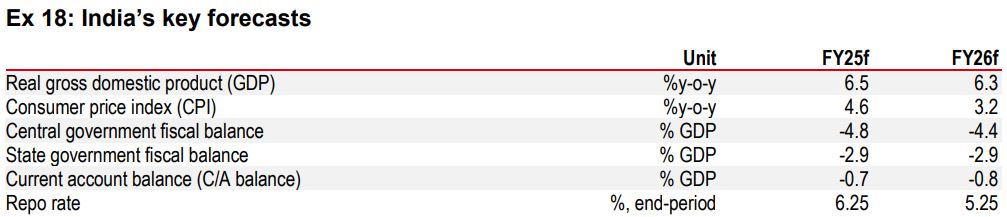

Why is this important? GDP growth has softened over the last few quarters (averaging 6.5% y-o-y over the last 4 quarters, versus 8.5% in the 8 quarters prior). We find a two-way causality, of credit growth impacting GDP growth and vice versa. So if credit growth can be pushed up, GDP growth could arguable rise over time.

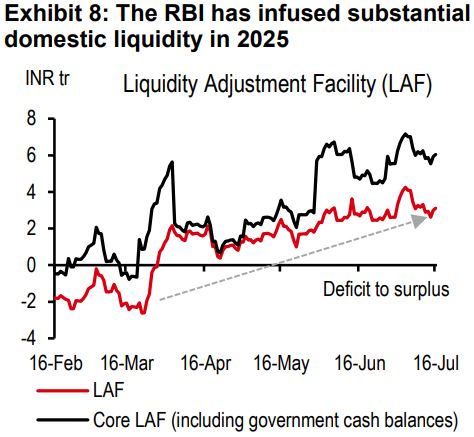

Can the RBI help? Yes, it can, and it has. The RBI has cut the repo rate as well as the CRR by 100bp each since early 2025. It has also infused domestic liquidity by cINR10tr (see exhibit 8).

The transmission of these rates has been off to a good start. On new loans, there is already a24bps transmission until May, by when the repo rate had been but by 50bps. Given another 50bps rep rate cut in June, transmission is likely to rise over subsequent months.

Will it solve the entire credit slowdown problem? Likely not. Because just as the deposit composition issue had its roots in the real economy last year, the credit softness issue has links to the real economy too.

Weaker growth has lowered the demand for credit. And more importantly, the changing composition of growth has played a role too.

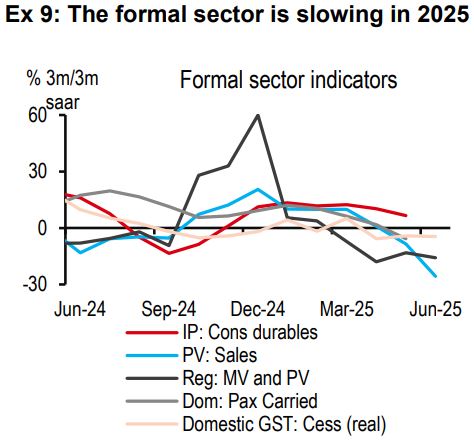

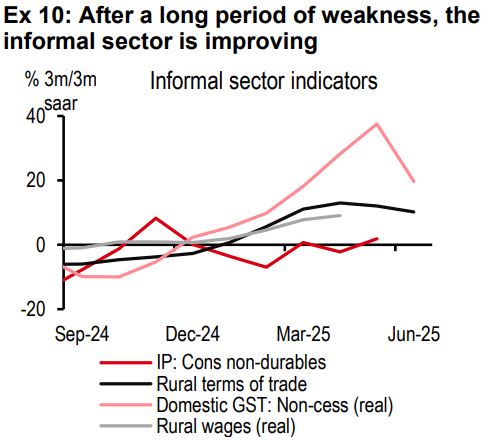

We find that after a few years of strong growth, the formal sector[@india-economics-05-02] is slowing in 2025. This is led by factors such as gains from strong equity markets and rising wage growth now plateauing after a strong run.

And after a long period of weakness, the informal sector[@india-economics-05-03] is improving, led by better weather events, improving farm incomes and falling inflation boosting purchasing power.

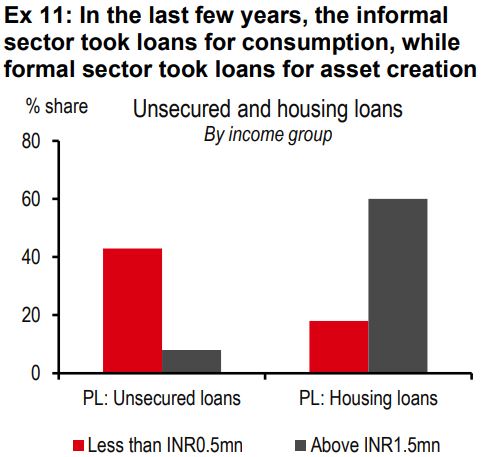

This pivot in growth composition from formal to informal can be a drag for credit growth. Let us explain. Until last year, the investment demand for credit was strong as households in the formal sector were investing in real estate. Meanwhile the consumption demand for credit was strong too, with households in the informal sector doing poorly and taking loans to meet consumption needs (see exhibit 11).

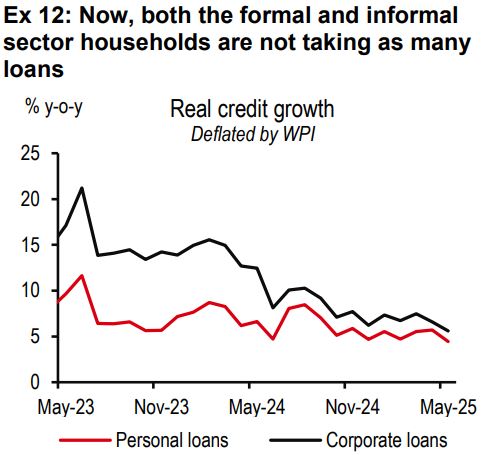

Now, with formal sector fortunes not rising as rapidly as before, this sector may be less willing to sign up for long-term financial debt such as housing loans, thereby slowing personal loan growth. Meanwhile, the informal sector, benefiting from higher real income, may not feel the need to take personal loans to fund consumption (see exhibit 12).

Credit growth is being squeezed from both ends. What’s the way out?

We find that the key driver of credit growth has changed over time, from supply of credit to demand for credit.

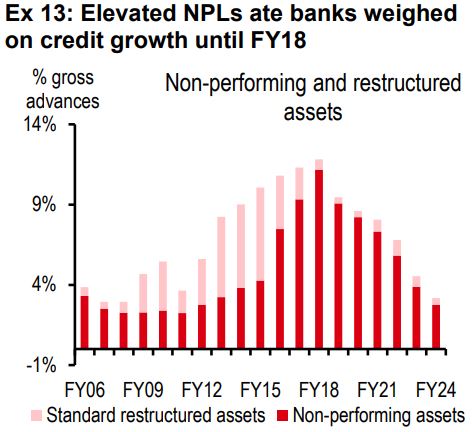

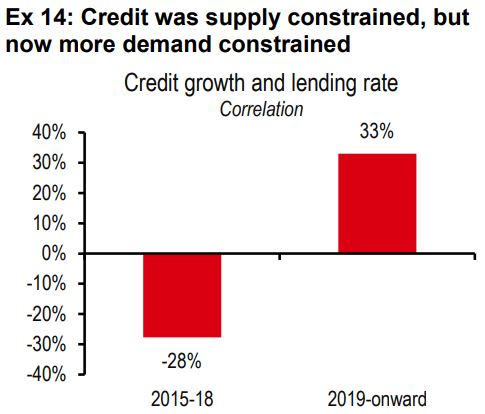

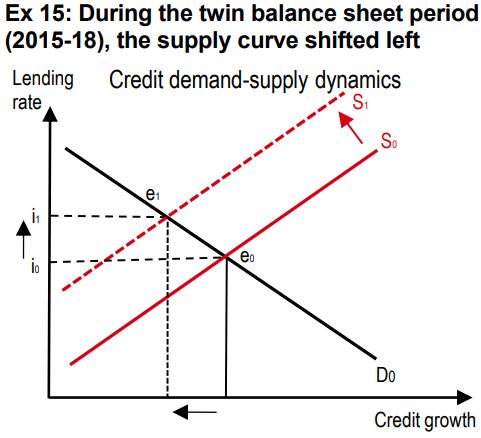

In the decade ending FY18, which was characterized by the twin balance sheet problem of too much NPLs at India’s banks, supply of credit was the problem (see exhibit 13). This can be seen clearly from a negative correlation between credit growth and lending rates (see exhibit 14). It basically means that the upward sloping supply of credit curve moved backward leading to lower credit growth but higher lending rates (see exhibit 15).

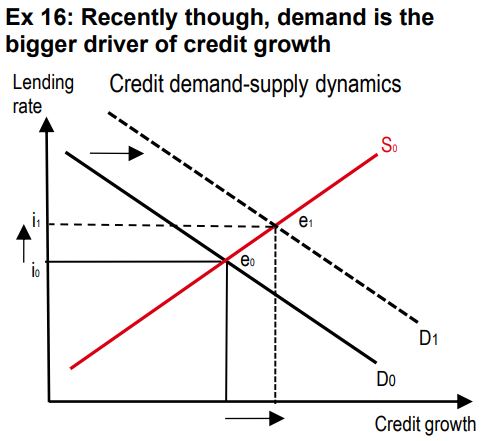

Following a painful period of asset quality recognition, the NPLs at banks were lowered, and supply side constraints eased. We find that in the subsequent period (FY18 onwards), the main driver of credit growth was demand for credit. Again, this can be seen clearly from a positive correlation between credit growth and lending rates (see exhibit 14 again). It basically means that the downward sloping demand for credit curve moved rightwards, leading to higher credit growth and higher lending rates (see exhibit 16).

At a time when demand is the main driver of credit growth, how does one encourage it?

The RBI can play a role, and indeed it has. The transmission of the policy rate cuts into lending rates is off to a good start, and as it progresses, will likely stoke demand for credit over the next few quarters.

But as discussed above, the current credit growth problem has its roots in real GDP growth, and more importantly, its composition. Addressing that will likely provide a bigger and more long-lasting solution, than continued RBI policy easing.

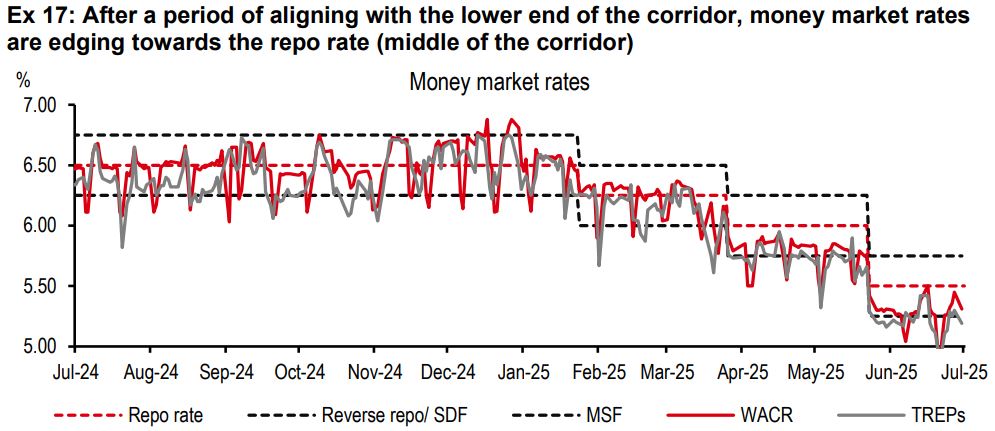

And we believe RBI knows this. After a period of policy easing, it is gently focusing back on normalization and macro stability. Recent steps in issuing VRRRs to take out some of the excess liquidity and align the call money rate more closely with the policy repo rate, in our view, speaks to that (see exhibit 17). Indeed, this alignment is a cornerstone of India’s inflation targeting regime.

So if RBI can’t hand-hold beyond a point, we need to find another way to spur the real economy. In the chicken-and-egg debate of who between the credit growth and GDP growth will rise first, we, thankfully, have a new contender – reforms.

At a time when global supply chains are getting rejigged once again, if India can do the right reforms and become a more meaningful producer and exporter of goods, that could spur investment and growth. This in turn could give a fillip to credit demand.

The opportunity is clear. As we have argued before, there is space for a new producer and exporter of mid-tech goods.

India can embrace this opportunity with its abundant labour and wage cost advantage. But to do this, we believe it needs the right reforms – lower tariff rates on intermediary inputs, more trade deals with other economies, more openness to FDI inflows, and more ease of doing business reforms across states.

Higher credit growth and GDP growth will likely follow, if India barks up the right tree of reforms, rather than waiting for RBI action to do the trick.

Additional disclosures

1. This report is dated as at 18 July 2025.

2. All market data included in this report are dated as at close 17 July 2025, unless a different date and/or a specific time of day is indicated in the report.

3. HSBC has procedures in place to identify and manage any potential conflicts of interest that arise in connection with its Research business. HSBC's analysts and its other staff who are involved in the preparation and dissemination of Research operate and have a management reporting line independent of HSBC's Investment Banking business. Information Barrier procedures are in place between the Investment Banking, Principal Trading, and Research businesses toensure that any confidential and/or price sensitive information is handled in an appropriate manner.

4. You are not permitted to use, for reference, any data in this document for the purpose of (i) determining the interest payable, or other sums due, under loan agreements or under other financial contracts or instruments, (ii) determining the price at which a financial instrument may be bought or sold or traded or redeemed, or the value of a financial instrument, and/or (iii) measuring the performance of afinancial instrument or of an investment fund.